4️⃣ Historic Shareholder Revolt Led By Church Activists Reaches Decisive Climax

GM shareholders witness automotive history and decide the fate of the company's future in South Africa. In the aftermath, a new industry is born that leads to economic revolution.

Part 4 of The Godfathers, a real-life story about a controversial church group’s campaign to end Apartheid that revolutionized the global economy. If you missed it, read my intro or start from Part 1.

Dear Walkers,

I’m so thankful that you’ve made it this far in The Godfathers. Today is the day we’ve all been waiting for as all the efforts of Tim Smith and church activists reaches a historic and dramatic climax. Today’s newsletter will make all the time you’ve invested in this story so worth it!

Keep walking,

Ryon Harms

The Godfathers (Part 4)

Moment of Truth

Chairman James M. Roche called to order the 93rd annual shareholder meeting of the General Motors Corporation. Tim Smith found a seat near some friends from the social activist group known as Campaign GM.

As the twenty three members of the GM board took the stage to resounding applause, the nearly two thousand attendees witnessed automotive history. Among the otherwise all-white group of men was the first African American ever appointed to the board of a company in the Fortune 500, and the first at any car company.

Dr. Leon H. Sullivan was head pastor of the large and influential Zion Baptist Church in Philadelphia. He famously organized hundreds of local ministers in a campaign to boycott white-owned businesses that refused to hire black workers. The “don’t buy where you don’t work” campaign resulted in tens of thousands of new opportunities for the black community. Church activists could not have dreamed of a better man to represent their interests on the GM board than the “Lion of Zion.”

Beyond his skin color, the rookie board member and six-foot five former college athlete stood out even more on stage next to the frail, ninety-five-year-old Charles Mott at his 59th annual meeting of the Board. The company patriarch had already been on the Board almost ten years when Leon Sullivan was born in a West Virginia slum.

Roche’s search for an African American board member likely began at the previous year’s shareholder meeting. Progressive iconoclast Ralph Nader publicly blasted the Chairman and filed resolutions to combat the company’s dismal record on civil rights, driver safety, and air pollution. “The persons affected by the corporation must be allowed to influence its decisions,” argued his group of legal activists from Campaign GM at the previous shareholder meeting. Less than three percent of shareholders had voted for their resolutions.

Why James Roche selected a black man to the board is unclear. Perhaps he was persuaded by social justice activists that an all-white board looked racist. Maybe he needed a public relations win after Nader's blistering bestseller, Unsafe at Any Speed. Perhaps it was the blowback from the drawn-out worker strike. Whatever the reason, he couldn’t just appoint any black man to the board of the world’s most powerful company.

Dr. Sullivan was more than a black religious leader and social justice activist. Following his boycott campaign in Philadelphia, Sullivan realized not enough black men and women were qualified for the thousands of new roles suddenly available. He founded the Opportunities Industrialization Centers, a job training program that had become the largest in the world by the time of the meeting. Sullivan represented the kind of “self-help” ethos for black empowerment that Roche wanted to project at GM.

Roche never credited activists for inspiring the appointment and denied their obvious influence to the press. Giving the “gadflies” too much credit would have opened the floodgates to more activism. Admitting that his company had bowed to outside pressure would have also detracted from the well-deserved respect of Dr. Leon Sullivan. Roche needed to blunt the inevitable chatter about how the pastor with no automotive experience had been a “diversity hire” selected solely based on skin color.

Upon his historic appointment to the GM board, Sullivan received a call from the outgoing President of the United States: "Leon, this is Lyndon [Johnson]. What's good for General Motors now really is good for America."

Roche and Sullivan appeared together on the cover of Time Magazine. On Meet the Press, Sullivan insisted he would not be an apologist for tokenism and would resign if black workers at GM had not made large and measurable gains under his watch. He also said, to the ecstatic joy of church activists, “I believe that America, itself, with its industries and business, can no longer underwrite apartheid . . . the United States government ought to declare an economic boycott against the Union of South Africa."

Tim Smith could have watched that interview a thousand times.

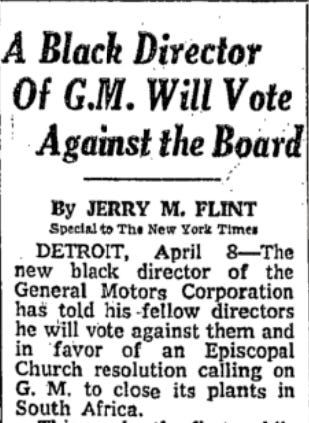

Sullivan made history again when he informed the rest of the GM board that he would vote against them and for the Episcopal Church’s resolution. Nobody on the board, not even Mott, could remember a time when a director had publicly disagreed with management on a resolution.

Beyond appointing Dr. Sullivan, which to Nader and activists was the only real progress, GM created a public policy committee to give matters of community concern "a permanent place on the highest level of management." It formed a committee of noted scientists to explore solutions to environmental problems and allocated millions to fight pollution from its cars and plants. It loaned a million dollars to support low-income housing and deposited millions more in black-controlled banks. Chairman Roche had prepared for round two with activists.

GM’s actions to address activist pressure unleashed a backlash from conservatives. Chief among them Milton Friedman, the highly influential economist from the Chicago School of Economics. Responding to calls for greater corporate social responsibility, the conservative firebrand published the “Friedman Doctrine” in the New York Times.

“What does it mean to say that ‘business’ has responsibilities?” demanded Friedman, “Only people can have responsibilities.” He saw the trend of executives bending to social activists as “unadulterated socialism.” Executives like Roche were “unwitting puppets” of the intellectual forces that were “undermining the basis of a free society.” He saw the millions being invested by corporations like GM on social causes as spending shareholder money without consent. Far from radical, Friedman’s view was a conservative vision of the status quo.

In a letter to the editor of the New York Times, another critic aimed at the church’s anti-apartheid resolution. He was a black, “card-carrying” Episcopalian that had visited South Africa. In his view, the church’s use of 12,000 shares out of 25 million was a clear case of the “flea trying to kill the elephant.” He lambasted the “white liberal establishment” for acting in the name of the oppressed without first consulting them.

James Roche advanced the mundane business on the agenda of the shareholder meeting and then came the moment of truth. It was time to hear directly from shareholders - the fireworks that activists and the press eagerly anticipated, and that everyone else there had dreaded.

Bishop Hines walked to the podium in the center aisle to address the Board. “To date there has been no indication that the American business presence has been a liberating force in South Africa.” Investments had grown fivefold in the region during a time “marked by the intensification and multiplication of repressive laws, and the gap between the average white and African wages has increased.” General Motors was “increasing the strength and control of the racist dictatorship.”

Defenders of the corporation groaned for all to hear. James Roche replied that no one favored Apartheid. “GM is convinced that the proper course is not to turn its back on a complex situation but to further the progress already being made, and through our operations, work to bring about progressive change.” Which, in a way, was what the churches were doing by engaging General Motors rather than selling its shares.

The treasurer of the American Baptist Home Mission Societies announced that the church had voted its 55,000 shares for the proposal to close South African plants. Adding, “when G.M. contributes to a government that is keeping a large segment of its population in virtual slavery, then we as shareholders with Christian conviction must urge that this arrangement be brought to an orderly end.”

A professor from Yale said large corporations were “oligarchies” working “unchecked” by outside forces. He warned that if Roche thought he could “go home and think this debate is over,” he was “delusional.”

Chairman Roche ran the meeting with a firm hand, cutting off several rambling activists. At times defenders of the corporation dominated the meeting.

Timothy Smith sensed the time had come and crossed the aisle toward the podium. He was less nervous than he had expected and “heartened” by having heard so many others defend his views. He told the Chairman about his trip to South Africa. He quoted plant managers on the lack of reasoning power and depth perception of black people.

More groans were heard.

It was misleading to say General Motors in South Africa was “apolitical,” explained Smith, when the company’s presence there had such a “strong political and economic effect” in favor of the status quo. General Motors helped diversify, stabilize, and made the apartheid regime self-sufficient.

Smith said his peace and felt satisfied he’d done everything humanly possible to persuade General Motors to leave South Africa.

Several grueling hours into the debate, Roche stumbled, “We are a public corporation owned by free, white…” It was only a millisecond, but the pause drew nervous laughter. Roche finished, “black, yellow and people all over the world.”

And then, Rev. Leon Sullivan rose to his great height and “very dramatically” walked off the stage toward the microphone. Once on the floor he turned around to address the Board directly as if he were a common shareholder.

"American industry cannot morally continue to do business in a country that so blatantly and ruthlessly and clearly maintains such dehumanizing practices against such large numbers of its people." His voice rose to an emotional peak in a baritone that a witness said resembled the late Dr. Martin Luther King: "I hear voices say to me, 'Things will work out in time -- things are getting better -- let us go slow on this matter! And I ask, why does the world always want to go slow when the rights of black men are at stake?”

Someone shouted, “Right on!”

“And although I know the position I take will lose today,” added Sullivan, “you can be sure that I shall continue to pursue it tomorrow until black people in the Union of South Africa are free.” Sullivan’s speech sparked the day’s loudest applause.

Tim Smith anxiously awaited the vote totals. No way the resolution would ever receive a majority vote, but would anyone beyond the churches vote for the resolution? Would the results be embarrassing or inspiring?

The Episcopal Church’s proposal for General Motors to withdraw its plants and investment in South Africa received support from … 1.29 percent of shares voted or about three million out of 227 million total shares. Put another way, 99 percent of shareholders supported GM continuing operations in South Africa. Shareholders had automatically voted for management at a time when the power of proxy voting had yet to be full understood.

It was a staggering loss, but not unexpected. South Africa was a world away and the lives of poor blacks were irrelevant to most shareholders. In the end, all that mattered to most investors were profits.

Still, church activists captured the moral high ground. They sparked a national conversation and forced the company to take a moral position in public. What had started as a few thousand shares became three million. And as Campaign GM showed, even a minor vote could spark progress. Activism was a game of inches and there was still time for a comeback.

Chairman Roche, who stood on stage for seven bruising hours, concluded:

“Over the last several years, I personally have been in a position to give serious thought to the pressures for change. General Motors, as we have tried to show, is responding to the demands of our society.” Adding, “I don't think we won a victory. I think we won a vote of confidence from our shareholders. I think we could lose that vote of confidence very quickly unless we respond in the way our shareholders expect us to do to these problems, and that is what we intend to do.”

What Timothy Smith, Bishop Hines, and Leon Sullivan could not have perceived in the moment was that the seeds they sowed made them the godfathers of a new industry that ultimately transformed the global economy.